Thrill and Sensation in the Themed Space

by Chip Limeburner

Perhaps best capturing the role of the senses in themed entertainment, Scott Lukas writes, “Theme parks give themselves a place by being spaces of hypersensation” (2008, 67). The act of placemaking—cultivating a space to have its own particular identity and feel—is central to themed entertainment. Whether elsewheres or elsewhens, designers carefully adjust features of a space to imbue it with identity, and although some of this identity may come in the form of an ineffable atmosphere (Bille 2024), much of it comes explicitly from the material, and therefore sensory, qualities of that space. (King and O’Boyle 2011; Grice 2016; Bielo 2018).

Anthropologists have taken this notion a step farther by arguing that a sense of place in any particular space is not simply the sum of static properties of that environment, but indeed the fleeting, dynamic, and entangled relationships between that space and all the people, things, and ideas contained within it (Pink 2015; Lynch 2024). The notion that guests are not only passively embodied receivers for sensory stimulation, but indeed, actively engaged in creating place within a themed space (i.e. emplacement), is crucial to understanding the negotiation of guest experience between designers of themed space, operational employees, and the guests themselves.

Despite spatial designers’ best efforts to dictate the visitor experience, the received experience is nonetheless shaped by the guest’s own cultural norms and personal background. That the senses are not simply unmediated conduits to the properties of our surrounding world, but a filter conditioned by our social and political positioning is well attested to in the literature (Fjellman 1992; Howes and Classen 2013; Pink 2015). Indeed, this cultural conditioning of the senses goes some ways to explaining the reaction to Disneyland Resort Paris, opened in 1992 to scathing reviews and protests as the park was found to be at odds with local customs (Lukas 2008). Likewise, Lynch, Howes, and French have observed broad cultural differences in gambling activities based on nuances of sensory experience such as an East Asian preference for the communality of table games over the auditory and haptic appeal of slot machines (2020).

Even beyond the notion of “culture” along conventional ethnic or national lines, Lukas has observed that the shift from 19th century amusement parks to 20th century theme parks follows a transition in the fundamental guest unit of park attendance. While the 19th century funfair was catering to couples and carousers looking for cheap thrills, the 20th century park pioneered by Disney welcomed the family unit, precipitating the stringent dress codes, absence of alcohol, and childlike aesthetics that would afront the French some decades later (Lukas 2008). These concerns are not to say we are impossibly blind to other sensory configuration than those under which we we’ve been conditioned—for instance Edensor proposes avenues for sensory defamiliarization as a means for broadening horizons (2024)—however a consideration of these cultural sensorial assumptions is necessary for any analysis of the themed space industry.

Finally, a guest’s own personal recollections temper the sensorial experience of place (Pink 2015). Theme park scholars have been quick to point out that not only do themed spaces remind visitors of other places and media (Fjellman 1992; King and O’Boyle 2011; Koehler 2017), such as Disney parks reminding guests transmedial of Disney movies, but that the success these parks is often tied to the parks reminding guests of their own past experiences of those same parks, often from childhood (Lukas 2008), as I found in my own visit to Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure park this past November:

Looking up, [...] children manning water cannons on the overlooking cliff are now noticeable. I’m grateful not to be soaked, but the setup reminds me of when they once had similar cannons overlooking the Popeye ride and my mother sprayed my father, brother, and me below—a favourite family story. (Fieldnotes, 29)

These three aspects of sensory inquiry—emplacement, the cultural conditioning of the senses, and memory—form the backbone of understanding themed spaces’ unique address of the guest, and so I will allude to them as appropriate in considering the aspects of leisure, consumption, and quasi-religious experience in such spaces.

“Stomach lurches as my plane touches down in Orlando. [...] I guess a plane is basically a ride without tracks” (Fieldnotes, 1). From the moment my flight is landing in Orlando, I’m already thinking about the sensorial profiles of the theme park. Helpfully, both the high-altitude vantage of the plane and the lurch of my stomach as it comes in to land parallel the most obvious sensory dimension of themed spaces: leisure. Citing attractions at 19th century Coney Island amusement parks, Scott Lukas identifies two sensory facets that elevated these newfound pleasure parks as premiere leisure centers of their day: height, and kinetics (2008).

The first of these, height, reflects the novel sensory experiences provided by early amusement parks. Rides such as the Ferris wheel offered broad vistas overlooking the local landscape, much like my flight to Florida, forming new perspectives of one’s surroundings.

While Edensor maintains that the careful design of amusement park rides likely does not truly destabilize the underlying culturally conditioned sensory schema (2024), it is nevertheless notable that not only the rides of early amusement parks, but also the very architecture of contemporary worlds fairs presented audiences with altogether foreign and unprecedented sensory experiences (Sally 2006; Lukas 2014).

The tension between the search for novel sensations and the re-assertion of established cultural conditioned sensoria is perhaps captured nowhere more strongly than in the consideration of thrill in amusement parks. Consisting of visceral sensations in response to kinaesthetic (Mohun 2001; Sally 2006) or strongly emotional stimuli (Lukas 2008), thrill is typically a response to a perceived danger of some kind, and scholars have grounded the pleasurable experience of danger in what they term “risk societies” (Mohun 2001)—cultures that develop elaborate practices of simulated risk in the face of heightened danger in quotidian life. In particular, scholars have noted that the rides of the fairground mimicked the machines of the factory, retreading the anxieties of industrialization in a newly controlled fashion (Mohun 2001; Sally 2006). Notably, though this parallel speaks to the pervasiveness of industrial structurings of the sensorium, Mohun underscores that guests were not content to simply interact with rides as their designers intended, but would “add[...] more thrills by trying to control the speed of the ride, by standing up and by engaging in a variety of other dangerous and unpredictable activities” (Mohun 2001, 292). This attempt to heighten the sensation of danger already present in the ride would lead to the invention of many safety features protecting guests from themselves as much as the forces of the ride system, but also speaks to a deeply-rooted sensation seeking that perhaps transgresses conditioned sensory expectations.

One of my friends points to a section of corkscrewed track that stretches out over the park’s lagoon, just meters from the water’s surface. “That’s the ‘mosasaurus roll’,” they say, “this coaster doesn’t hold any records [...] but something about that stretch you just really feel like you’re going in the water.” Tensions rise as we make it to the indoor part of the queue and signage insists all personal belongings [...] must be stored in lockers for the safety of all involved. [...] (Fieldnotes, 30-31)

Approaching the mosasaurus roll, I grip the handles on my lap bar tightly and am horrified as half my fellow riders stretch out their arms, as though hoping to touch the water below [...] (Fieldnotes, 33-34)

The above description from my own encounter with the Velocicoaster at Universal Studios’ Island of Adventure park illustrates both the company’s clear desire to avoid anything or anyone actual falling out of the ride vehicle despite the simulated risk, yet at the same time captures patron attempts to heighten the very sense they’ll go careening into the park’s lagoon midway through the ride—an authoritative attempt at conditioning the senses, and an oft observed rebuttal.

The commodification of risk found in themed spaces is, of course, not restricted to thrill rides at amusement parks. In fact, perhaps the industry most famed for both its commodification of risk and premiere themed spaces is that of the casino. Encapsulated most strongly in the urban landscape of Las Vegas, Nevada and its strip of themed hotel-casino blocks (Fox 2005; Lukas 2007; Lynch, Howes, and French 2020), casinos have developed their own architectural vocabulary for transporting the patron and hi-jacking the senses (Lynch, Howes, and French 2020). Through the haptic, visual, and auditory enticement of slot machines and game tables, opportunities to gamble draw the viewer, while labyrinthine and circuitous space forces visitors to walk the long way round past all these distractions (Lynch, Howes, and French 2020). This garden path past all the tantalizing opportunities the venue has to offer is indeed not entirely dissimilar from the liminal arcades of a mall (Crawford 1992; Lukas 2008) or winding walkways of a theme park (King and O’Boyle 2011)—keeping patrons moving forward toward some goal, but at a meandering pace more accommodating to making a few pit stops along the way. While in the casino case, it can almost seem as if business owners are trying to keep visitors trapped within the building’s walls, in the theme park, oblique sightlines and tight spaces offer opportunities for curious exploration:

Traversing on through the Jurassic Park land [in Islands of Adventure], we pass by a dino excavation-themed playground [...] and soon enough the three of us are trekking up craggy stairs, across rickety rope bridges, and through damp caverns (Fieldnotes, 26)

[...] we continue on through the caves, discovering new hidden treasures in every crevice. Fake amber [...] acts as stained glass letting streams of amber light into one hallway, and in another cul-de-sac we discover an “echo cave” that repeats back to us anything we call into it. (Fieldnotes, 28)

The models of the casino and theme park playground are intriguing as in neither case is there strictly a commodity or service being sold. This places both within a paradigm of what Pine and Gilmore term “the experience economy”, where at the time of their writing the manner in which a product was being sold was taking on new immersive and sensory qualities to encourage a sale, and acknowledging the popularity of theme parks, the authors prognosticate that soon enough, many businesses would be selling simply the experience itself (1998). In these cases, the rich and particular sensory texture of how we spend our time is the “product” we pay for.

This is not to say, however, that themed spaces don’t also still employ the previous model described by Pine and Gilmore for leveraging sensory experience to move tangible products. The gift shop is the premiere model of this in theme parks, filtering guests through shops before they can fully exit any given ride (Fjellman 1992). Typically, the fresh memory of the ride the guests just rode is used to push merchandise for the same intellectual property, and in some cases, as mementos of the ride experience itself:

Standing in the indoor queue for the [E.T.] ride, our surroundings are themed like a forest and the scent of pine hangs thick in the air. (Fieldnotes, 37-38)

At the other end [of the ride] we exit to the ride’s gift shop where we find a series of [scented] candles [...] I pull down another scented candle for the E.T. ride we just exited and I’m immediately bombarded by the overpowering scent of pine” (Fieldnotes, 39-40)

The described ET-queue-scented candle lets visitors take a little sensory part of the ride home with them—a means of not only using experience to sell commodity, but to, in fact, render the experience itself a crystallized commodity. Though the economic ouroboros here may be eating its own tail, the candle that guests take home with them speaks to rich fan practices of theming their own spaces, opening new possibilities for fan-determined negotiation of their favourite rides outside the watchful eye of park operators.

These heightened experiences, strong enough to not only carry a fee, but provoke return visits as well, become highly ritualized through repetition, eliciting a kind of quasi-religious devotion to consumption (Howes and Classen 2013). It should therefore be of little surprise that many scholars characterize the repeated return to theme parks, religious and secular alike, as a kind of pilgrimage (Fjellman 1992; Lukas 2008; Koehler 2017; Bielo 2018).

Writing of the theme park visit, Scott Lukas claims, “the first sense that the guest experiences is one of awe” (2014, 395). The capacity for the themed space to evoke awe is well attested, and while the senses of the skin may not be as truly an unmediated as we think, given the cultural conditioning of the sensorium (Howes and Classen 2013), many scholars nevertheless recognize that the awe inspired by highly immersive environments derives from a “testimony of the body” (Bielo 2020, 108) whereby we naturally trust “raw” sense experience more so than the written or spoken word. In some circumstances, the climactic shift in temperature and humidity felt on the skin and brought on by a fountain show in the Nevada desert can ostensibly attest to the god-like powers of industry (Fox 2005). In other circumstances, as Caroline Jones observes in drawing upon a 19th century allegory of a blind man at a world’s fair, the intimate smells, sounds, and haptic feel of the machines that drove the industrial revolution “penetrate the very body of their subjects with sublime shivers” (Jones 2016, 22). This haptic experience of communion with the machine parallels my own experience with the Incredible Hulk Coaster on my visit to Universal Studios; Islands of Adventure:

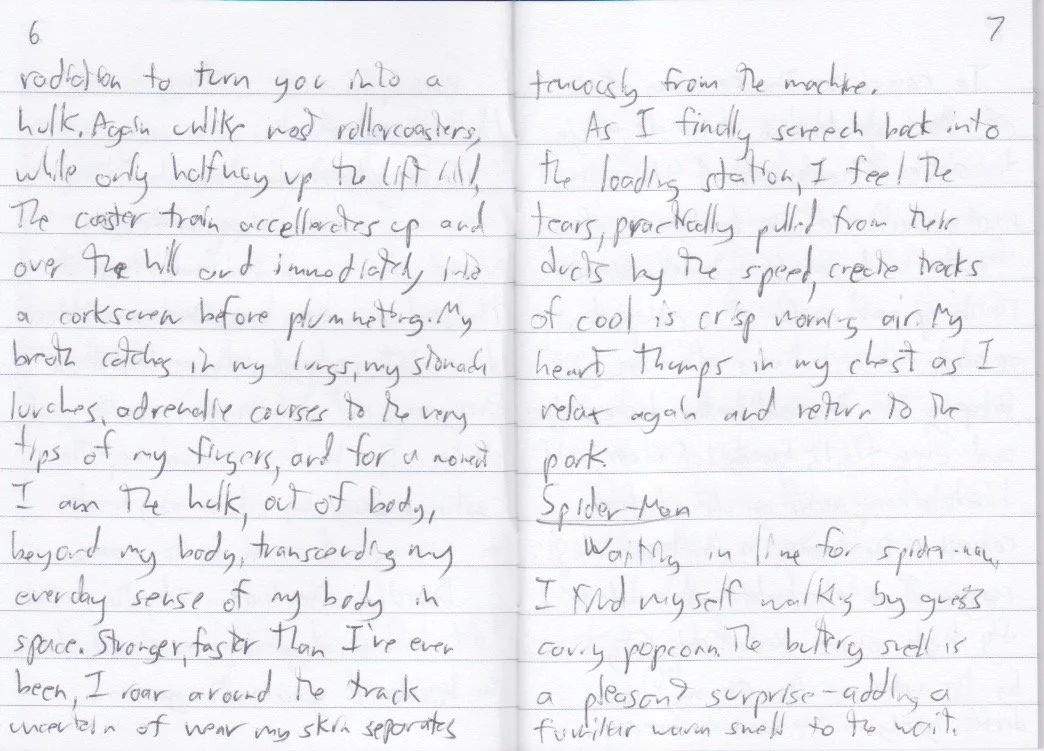

[...] halfway up the lift hill, the [Incredible Hulk] coaster train accelerates up and over the hill and immediately into a corkscrew before plummeting. My breath catches in my lungs, my stomach lurches, adrenaline courses to the very tips of my fingers, and for a moment I am the Hulk, out of body, beyond my body, transcending my everyday sense of my body in space. Stronger, faster than I’ve ever been, I roar around the track uncertain of where my skin separates tenuously from machine (Fieldnotes, 6-7)

Caught between interoceptive sensations, and the physical forces exerted from the outside, my own sense of separation from the feeling machine driving the experience begins to break down. The sensorium may be mediated by our experiences, but this conditioning only gives it all the more sway over our perceptions.

Whether for leisure, economic consumption, or quasi-religious awe, theme park designers endeavour to manipulate the guest’s senses to evoke other places and times. Despite this attempt at authoritative sensory experience, patrons nevertheless negotiate their reception through cultural and personal experience, as well as fan practices that heighten and alter sensory experience to match their desires. In this fashion, the theme park may be read through the complex network of overlapping stakeholder considerations that turn parks from undifferentiated space, to meaningful place.

Figure 1: Fieldnotes Sample.

Bibliography

Bielo, James S. 2018. Ark Encounter: The Making of a Creationist Theme Park. New York: New York University Press.

———. 2020. “Experiential Design and Religious Publicity at D.C.’s Museum of the Bible.” The Senses and Society 15 (1): 98–113.

Bille, Mikkel. 2024 “Talking about felt spaces: On vagueness and clarity in interviews.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Sensory Ethnography edited by Phillip Vannini. London: Routledge.

Crawford, Margaret. 1992. “The World in a Shopping Mall.” In Variations on a theme park: the new American city and the end of public space, ed. by Michael Sorkin. New York: Hill and Wang.

Edensor, Tim. 2024. “Defamiliarizing the sensory.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Sensory Ethnography edited by Phillip Vannini. London: Routledge.

Fjellman, Stephen M. 1992. Vinyl Leaves: Walt Disney World and America. Institutional Structures of Feeling. Boulder: Westview Press.

Fox, William L. 2005. In the Desert of Desire : Las Vegas and the Culture of Spectacle. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Grice, Gordon S. 2016. “Sensory Design in Immersive Environments.” In A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces, edited by Scott A. Lukas. Pittsburgh, PA: ETC Press.

Howes, David and Constance Classen. 2013. “Marketing and Psychology.” In Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses In Society. London: Routledge.

Jones, Caroline A. 2016. The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience. University of Chicago Press.

King, Margaret J. and J. G. O’Boyle. 2011. “The Theme Park: The Art of Time and Space.” In Disneyland and Culture: Essays on the Parks and Their Influence, edited by Kathy Merlock Jackson, and Mark I. West. Jefferson, N.C. ; London: McFarland & Co.

Koehler, Dorene. 2017. The Mouse and the Myth: Sacred Art and Secular Ritual at Disneyland. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Lukas, Scott A. 2007. “Theming as Sensory Phenomenon: Discovering the Senses on the Las Vegas Strip.” In The Themed Space: Locating Culture, Nation, and Self, edited by Scott A. Lukas. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

———. 2008. Theme Park. Objekt. London: Reaktion Books.

———. 2014. “How the Theme Park Got Its Power: The World’s Fair as Cultural Form.” In Meet Me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader, edited by Laura Holden, Hollengreen, Celia Pearce, Rebecca Rouse, and Bobby Schweizer. Pittsburgh, PA: ETC Press.

Lynch, Erin, David Howes, and Martin French. 2020. “A Touch of Luck and a ‘Real Taste of Vegas’: A Sensory Ethnography of the Montreal Casino.” The Senses and Society 15 (2): 192–215.

Lynch, Erin E. 2024. “Constellations of (Sensual) Relations: Space, atmosphere, and sensory design.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Sensory Ethnography edited by Phillip Vannini. London: Routledge.

Mohun, A. P. 2001. “Designed for Thrills and Safety: Amusement Parks and the Commodification of Risk, 1880-1929.” Journal of Design History 14 (4): 291–306.

Pine II, B Joseph, and James H. Gilmore. 1998. “Welcome to the Experience Economy.” Harvard Business Review 76 (4): 97–105.

Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. Sally, Lynn. 2006. “Fantasy Lands and Kinesthetic Thrills: Sensorial Consumption, the Shock of Modernity and Spectacle as Total-Body Experience at Coney Island.” The Senses and Society 1 (3): 293–309.